- Free Consultation 24/7: (813) 727-7159 Tap Here To Call Us

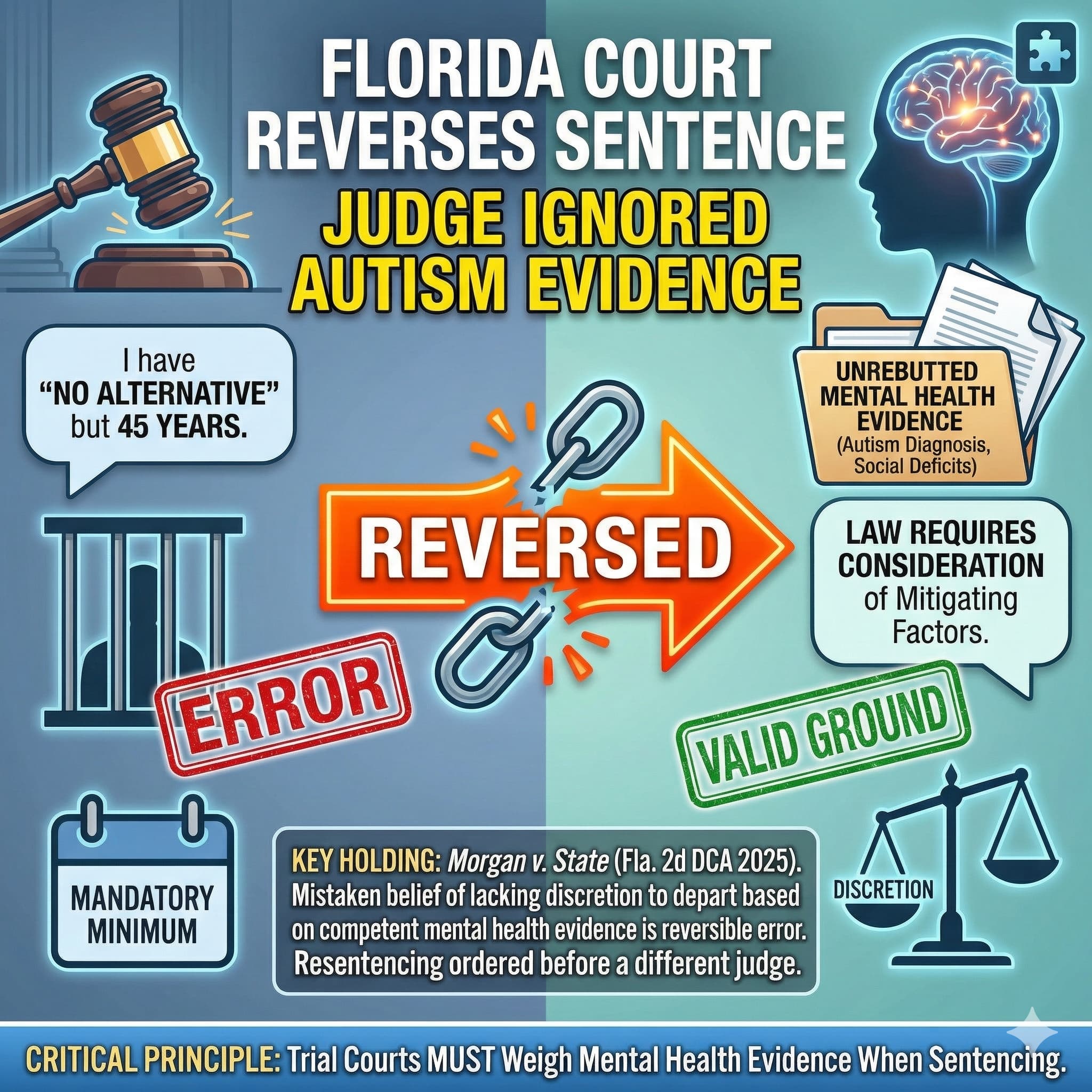

Florida Court Reverses Sentence: Judge Ignored Autism Evidence

Morgan v. State Reinforces That Trial Courts Must Consider Mental Health Evidence When Sentencing

| KEY HOLDING: MORGAN V. STATE (FLA. 2D DCA DEC. 31, 2025) When a defendant presents unrebutted evidence supporting a downward departure—such as an autism diagnosis with documented social deficits and compulsive behaviors—the trial court commits reversible error if it mistakenly believes it has “no alternative” but to impose the guidelines sentence. The Second DCA reversed and ordered resentencing before a different judge. |

When Judges Believe They Have No Choice

What happens when a defendant presents compelling mental health evidence at sentencing, but the judge ignores it? In Morgan v. State, decided December 31, 2025, Florida’s Second District Court of Appeal answered that question: the sentence gets reversed.

Winston Morgan faced serious charges—forty counts of possession of child pornography and one count of transmission. He pleaded no contest. Under Florida’s Criminal Punishment Code, his scoresheet called for a minimum sentence of nearly 45 years in prison. However, Morgan’s defense team presented unrebutted evidence at an evidentiary hearing over two days: Morgan had been diagnosed with autism, and his condition included documented social deficits along with compulsive, repetitive, and obsessive features inherent to that diagnosis.

The State did not rebut this evidence. Nevertheless, the trial court denied the motion for downward departure, stating it had “no alternative” but to sentence Morgan according to his scoresheet. That statement was legally incorrect—and it cost the trial court its sentence.

| The trial court’s fundamental error: believing it lacked discretion when, in fact, a valid legal ground for departure existed and was supported by competent, substantial evidence. When a judge mistakenly believes the law ties their hands, the appellate court must reverse. |

The Two-Step Test for Downward Departure

Florida law permits judges to impose sentences below the guidelines minimum when mitigating circumstances exist. The process is governed by Banks v. State, 732 So. 2d 1065 (Fla. 1999), which established a two-step test:

| Step | Question | Standard |

| Step 1 | CAN the court depart? Is there a valid legal ground with adequate factual support? | Mixed question of law and fact; requires competent, substantial evidence (preponderance standard) |

| Step 2 | SHOULD the court depart? Is departure the best sentencing option given the totality of circumstances? | Discretionary judgment call; reviewed for abuse of discretion |

The critical distinction: Step 1 asks whether the court has the legal authority to depart. Step 2 asks whether it should exercise that authority. A trial court that never reaches Step 2 because it mistakenly believes it failed Step 1 has committed reversible error.

| CRITICAL LEGAL PRINCIPLE “Where the trial court erroneously believes that it legally does not have the discretion to depart, the reviewing court must reverse the sentence.” — Soto v. State, 377 So. 3d 1232 (Fla. 2d DCA 2024) |

What Went Wrong in Morgan

Morgan’s defense team argued for a downward departure on multiple grounds, including his autism diagnosis. They presented unrebutted expert evidence over two days documenting his condition—the social deficits, the compulsive and repetitive behaviors, the obsessive features that are inherent to autism spectrum disorder.

At the conclusion of the hearing, the trial court made a critical misstatement: “The only way around the bottom of the guidelines is to make a determination that [Mr. Morgan] qualifies for a downward departure under [section] 921.0026. And what’s been argued before the Court today is a downward departure for youthful offender.”

This was factually incorrect. The defense had argued for departure based on Morgan’s autism—not just the youthful offender ground. The trial court then ruled: “I don’t think it’s appropriate for me to sentence [Mr. Morgan] as a youthful offender. Which leaves me with no alternative but to sentence him on Counts I through XLIV to 536.550 months.”

| THE TRIAL COURT’S ERROR The judge characterized the record incorrectly, stating that only the youthful offender ground had been argued. Because of this misconstruction, the court believed it had “no alternative” but to impose the guidelines sentence. In reality, competent substantial evidence supported a departure based on Morgan’s autism diagnosis—evidence the State never rebutted. |

Mental Health Conditions as Grounds for Departure

Section 921.0026, Florida Statutes, lists specific mitigating circumstances that can support a downward departure. However, the Second DCA emphasized a crucial point: this list is not exhaustive.

| “[T]he trial court can impose a downward departure sentence for reasons not delineated in section 921.0026(2), so long as the reason given is supported by competent, substantial evidence and is not otherwise prohibited.” — Coto v. State, 366 So. 3d 1 (Fla. 4th DCA 2023) |

This means mental health conditions like autism, when properly documented and presented with expert testimony, can serve as valid grounds for departure—even if not specifically listed in the statute. The key requirements are competent, substantial evidence and a logical connection between the condition and the appropriateness of a reduced sentence.

Statutory Mitigating Factors Under § 921.0026(2)

| Section | Mitigating Factor |

| (2)(c) | The capacity of the defendant to appreciate the criminal nature of the conduct or to conform that conduct to the requirements of law was substantially impaired |

| (2)(d) | The defendant requires specialized treatment for a mental disorder that is unrelated to substance abuse or addiction |

| (2)(i) | The offense was committed in an unsophisticated manner and was an isolated incident for which the defendant has shown remorse |

| (2)(j) | The defendant was too young to appreciate the consequences of the offense |

| Other | Any other factor supported by competent, substantial evidence that is not otherwise prohibited (per Coto v. State) |

The Remedy: Resentencing Before a Different Judge

The Second DCA did not merely reverse Morgan’s sentence—it ordered resentencing before a different judge. This remedy, while not automatic, is appropriate when the original sentencing judge has demonstrated a fundamental misunderstanding of the applicable law or the record.

The court cited Barnhill v. State, 140 So. 3d 1055 (Fla. 2d DCA 2014). In that case, the Second DCA reversed and remanded for resentencing before a different judge because the trial court failed to apply the Banks test to determine if the defendant qualified for a downward departure.

| THE OUTCOME Morgan’s sentence was reversed. He will receive a new sentencing hearing before a different judge—one who must properly consider whether his autism diagnosis and its documented features support a downward departure from the guidelines minimum. |

What This Means for Defendants with Mental Health Conditions

Morgan v. State reinforces several important principles for defendants facing serious charges who have documented mental health conditions:

First, present evidence at an evidentiary hearing. Morgan’s defense team held a two-day evidentiary hearing with expert testimony about his autism diagnosis. This created a record the appellate court could review.

Second, ensure the evidence is unrebutted if possible. The State presented no contrary evidence regarding Morgan’s diagnosis. Unrebutted evidence of a mitigating factor is powerful on appeal.

Third, make the record clear. Defense counsel explicitly argued for departure based on the autism diagnosis. When the trial court misstated the record, the appellate court had clear evidence of the error.

Fourth, understand that the statutory list is not exhaustive. Mental health conditions not specifically listed in § 921.0026(2) can still support departure if competent, substantial evidence establishes a basis for mitigation.

| WARNING FOR DEFENDANTS A trial court may properly consider mitigating evidence and still deny a departure at Step 2 of the Banks test. The key is that the court must actually consider the evidence and exercise its discretion—not mistakenly believe it lacks the authority to depart. If your judge says they have “no choice” or “no alternative” despite evidence supporting departure, that statement may be grounds for appeal. |

Frequently Asked Questions: Downward Departure in Florida

A downward departure falls below the minimum sentence Florida’s Criminal Punishment Code scoresheet recommends. Under § 921.0026, Florida Statutes, judges exercise discretion to impose lower sentences when competent, substantial evidence supports mitigating circumstances.

Yes. As Morgan v. State demonstrates, autism and other mental health conditions can support a downward departure when properly documented with expert evidence. Moreover, the statutory list of mitigating factors is not exhaustive—courts can depart for reasons not specifically listed in the statute, as long as competent, substantial evidence supports the departure.

The Banks test, established in Banks v. State, 732 So. 2d 1065 (Fla. 1999), requires two steps. First, the court determines whether it CAN depart—whether a valid legal ground exists with adequate factual support. Second, the court determines whether it SHOULD depart by weighing the totality of circumstances. A court that skips Step 2 because it mistakenly believes Step 1 was not satisfied commits reversible error.

When the defense presents evidence supporting a departure, a judge commits reversible error by claiming they have ‘no alternative’ or ‘no choice.’ In such cases, the judge fails to exercise the legal discretion the law requires. As the Second DCA held in Soto v. State, “Where the trial court erroneously believes that it legally does not have the discretion to depart, the reviewing court must reverse the sentence.”

In some cases, yes. When the original sentencing judge demonstrated a fundamental misunderstanding of the law or the record, appellate courts may order resentencing before a different judge. In Morgan, the Second DCA ordered exactly this remedy, citing Barnhill v. State as precedent.

The defendant bears the burden of proving mitigating factors by a preponderance of the evidence. This typically requires an evidentiary hearing with expert testimony—psychiatric evaluations, psychological testing, medical records, and professional opinions connecting the condition to the appropriateness of a reduced sentence. An experienced criminal defense attorney can help identify the right experts and present this evidence effectively.

| Facing Serious Charges? Mental Health Evidence Could Change Your Sentence. Tampa Criminal Defense Attorney Rocky Brancato has over 25 years of experience presenting mitigating evidence at sentencing hearings. As former Chief Operations Officer of the Hillsborough County Public Defender’s Office, he understands how to build a compelling case for downward departure—and how to preserve issues for appeal when trial courts err. Call (813) 727-7159 Confidential Consultation | The Brancato Law Firm, P.A. |

620 E. Twiggs Street, Suite 205, Tampa, FL 33602

Serving Hillsborough, Pinellas, and Pasco Counties