- Free Consultation 24/7: (813) 727-7159 Tap Here To Call Us

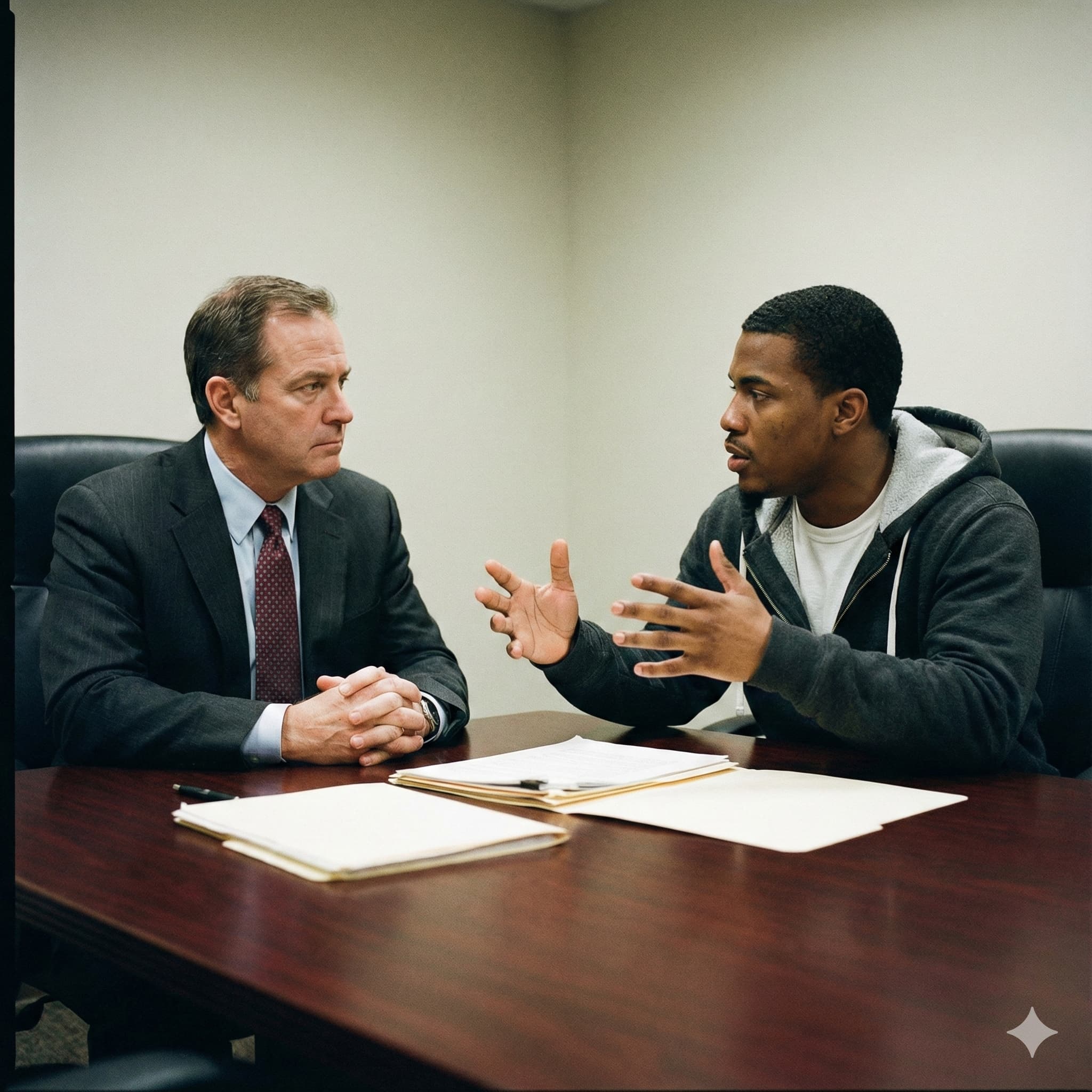

It’s the Client’s Call

A Tampa Criminal Defense Case Study

By Rocky Brancato

One of the most important principles in criminal defense is one that clients don’t always understand at first: it’s your case, not mine.

My job is to advise you. I tell you what the evidence shows, what the law says, what the likely outcomes are, and what I think you should do. I give you the benefit of 25 years of experience in Tampa’s criminal courts. You get the truth, even when it’s not what you want to hear.

But at the end of the day, the decision is yours. You decide whether to take a plea or go to trial. You decide whether to testify. The amount of risk you are willing to assume is yours. It’s your liberty on the line, your life that will be affected by the outcome. I can guide you, but I can’t make the decision for you.

And sometimes, the client makes a different choice than I would have recommended.

Sometimes they’re wrong. But sometimes—like in the case I’m about to tell you about—they’re right.

The Case

My client was charged with cocaine possession. The facts, on their face, looked bad for him.

He had experienced a medical emergency and was transported to the hospital. When hospital personnel removed his clothes for treatment, they discovered cocaine in his pants pocket—along with his wallet containing his identification and money. The hospital stored his belongings, and when the cocaine was discovered, they reported it to law enforcement.

The State was able to establish chain of custody. The cocaine was real. It was in his pants. His wallet—with his ID—was in the same pocket. Those facts weren’t in dispute.

The State offered a plea deal. Under the circumstances—the evidence, the charge, the likely outcome at trial—I thought he should take it. I told him so directly. That’s my job: to give honest advice, not to tell clients what they want to hear.

He looked at me and said no. He wanted to fight.

| The Client’s Right to Decide When a client rejects my recommendation, I don’t argue. I explain my reasoning, make sure they understand the risks, and then I respect their decision. It’s their life. And once they’ve made the call, my job is to fight as hard as I can to win—regardless of what I would have done in their position. |

The State’s Case

The State’s theory was straightforward: actual possession.

Under Florida law, actual possession means the drugs were on your person—in your hand, in your pocket, under your direct physical control. The cocaine was in my client’s pants. His pants were on his body. His wallet with his ID was in the same pocket. Open and shut.

And technically, the State was right. He was in actual possession. The drugs were on him. When he was conscious, he had dominion and control over his own pants and whatever was in them.

This was the kind of case where most defense attorneys would tell their client there’s nothing to fight. The drugs were on you. They can prove it. Take the deal.

But I’ve been doing this for 25 years. And experience teaches you to look for what’s not obvious.

Seeing What Others Miss

When I reviewed the evidence, I noticed something that the State apparently hadn’t considered significant:

No one ever saw my client with conscious dominion and control over the cocaine.

Think about it. The drugs were discovered by hospital staff after he was already incapacitated from a medical emergency. By the time anyone found the cocaine, he was unconscious or being treated. No witness could testify that they saw him reach into his pocket. There was no witness who saw him touch the drugs. No one saw him conscious and in control of the cocaine at any point.

The State could prove the drugs were in his pants. They could prove chain of custody. They could prove actual possession in the technical sense—the drugs were on his person.

But could they prove he knowingly possessed them? Could they prove conscious dominion and control?

That was the gap. And gaps create reasonable doubt.

“Constructive Spiritual Possession”

I needed to frame this argument in a way the jury would understand and remember. Legal distinctions can sound abstract. Jurors need something concrete—something that sticks.

So I coined a phrase: “constructive spiritual possession.”

The argument went like this: Yes, the cocaine was in his pants. Yes, those pants were on his body. But the State is asking you to convict him of knowingly possessing those drugs, and the only evidence they have is that the drugs were found on an unconscious man being treated for a medical emergency.

No one saw him conscious with those drugs. No one saw him exercise knowing control. The State wants you to infer possession from proximity—to assume that because the drugs were in his pants, he must have known they were there and must have been in control of them.

But that’s not proof. That’s speculation. That’s constructive spiritual possession—the drugs were in the same space as his body, so he must be guilty. Is that enough to take away someone’s freedom?

| The State proved proximity. They proved the drugs were in his pants. But they never proved conscious, knowing possession—because no one ever witnessed it. And in a criminal case, the State has to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Not assume it. Not infer it. Prove it. |

Preparing the Client to Testify

There was another factor in this case: my client wanted to testify.

This is always a risk. When a defendant takes the stand, they open themselves up to cross-examination. The prosecutor’s job is to rattle them—to get them angry, confused, or defensive. To make them say something they shouldn’t. Many defendants hurt their own cases by testifying.

But again—it’s the client’s call. The decision whether to testify belongs to the defendant, not the attorney.

So I prepared him. I gave him rules for testifying: Answer the question you’re asked, nothing more. Don’t volunteer information. Stay calm. Listen to the entire question before answering.

And I warned him: The prosecutor is going to try to make you angry. That’s the strategy. They want you to lose your temper, to get defensive, to slip up. Don’t take the bait.

He listened. He heeded the advice.

On the stand, he was calm. He was composed. He answered the questions directly without being evasive. When the prosecutor pushed, he didn’t push back—he stayed measured. He told his story in a way that was credible and human.

His performance on the stand, combined with my argument about the absence of any witness to conscious possession, gave the jury what they needed.

The Verdict

The jury came back: Not guilty.

Cocaine in his pants. His wallet with his ID in the same pocket. Chain of custody established. And a not guilty verdict.

If my client had followed my recommendation, he would have taken the plea. He would have a drug conviction on his record today. Instead, he walked out of that courtroom with his record clean.

He made the call. I made the argument. He executed on the stand. And together, we won.

The Lesson

This case reminds me of two things.

First: respect client autonomy. I’ve been doing this for 25 years. I know the statistics, I’ve seen the patterns, I have a sense of how cases tend to go. But I don’t know everything. Sometimes the client sees something I don’t—maybe it’s confidence in their own ability to testify, maybe it’s a willingness to take a risk I wouldn’t take, maybe it’s just the conviction that they can live with a loss but can’t live with giving up without a fight.

Second: see what’s not obvious. The State saw a slam dunk—drugs in his pants, wallet with his ID, chain of custody. What they didn’t see, because they weren’t looking, was the absence of any witness to conscious possession. That gap was there the whole time. It just took an attorney who knew how to find it and how to make a jury see it.

| The Attorney’s Role A good criminal defense attorney gives honest advice—including advice the client doesn’t want to hear. But a good attorney also respects the client’s right to make their own decisions. And when the client decides to fight, a good attorney finds the argument that wins. |

What This Means for You

If you’re facing criminal charges, you need an attorney who will be honest with you—who will tell you the truth about your case, even when it’s uncomfortable. You need someone who will give you real advice based on experience, not just tell you what you want to hear.

But you also need an attorney who respects your right to make decisions. Who won’t pressure you into a plea deal because it’s easier for them. Who, when you decide to fight, will fight with everything they have.

And you need an attorney who can see what others miss. Who can find the gap in the State’s case when everyone else sees a slam dunk. Who knows how to frame an argument so a jury understands it and remembers it.

About the Author

Tampa Attorney Rocky Brancato is the founding attorney of The Brancato Law Firm, P.A., a criminal defense practice in Tampa, Florida. With more than 25 years of experience—including service as Chief Operations Officer of the Hillsborough County Public Defender’s Office—Rocky has tried hundreds of cases and developed a reputation for finding what others miss. He believes in honest advice and client autonomy: your case, your decision, his fight.

| Facing Criminal Charges? It’s Your Call. Call (813) 727-7159 The Brancato Law Firm, P.A. | Tampa, Florida |